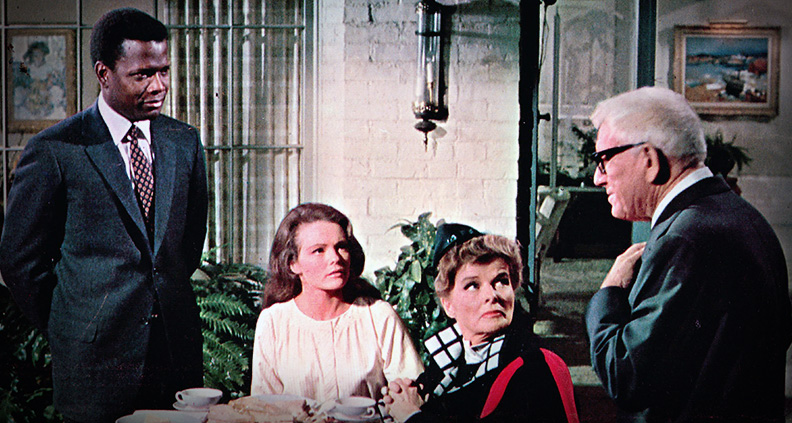

In 1967, just six months after the Loving v. Virginia civil rights decision struck down interracial marriage bans across the US, Stanley Kramer’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? became a critical-and-box-office hit. The film revolves around John Prentice, played by Sidney Poitier, as a successful black doctor meeting his white fiancé Joey’s (Katharine Houghton) parents for the first time. Fifty years later, The Big Sick—directed by Michael Showalter and produced by Judd Apatow—centered on yet another culture-clash relationship, this time set in the present day. Based on the actual lives of star Kumail Nanjiani and spouse/co-writer Emily V. Gordon, the film follows a Pakistani-American stand-up comedian as he falls in love with a white grad student, played by Zoe Kazan. Both of these comedy-dramas explore the cognitive dissonance people often experience when it comes to entering into a type of relationship that, for whatever reason, is frowned upon by others. “Cognitive dissonance” has been a buzz term in the sociopolitical arena lately, with good reason. The concept explains the mental discomfort people feel when they hold contradictory beliefs. As a result, they will try to change or justify one of the beliefs over the other or actively avoid social situations that force them into confrontation. In Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? Joey’s parents, Matt and Christina (Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn) experience this discomfort. While the progressive liberal couple raised their daughter to be colorblind and to denounce the notion that the white race is superior to the black, Matt especially struggles to accept their daughter’s decision to marry a black man. And they aren’t the only ones. Tillie, the family’s African American maid, finds herself indignant at the thought of Dr. Prentice marrying her little Joey, saying, “Civil rights is one thing. This here is somethin’ else.” In The Big Sick, the person most conflicted about Kumail and Emily’s relationship is Kumail himself. He loves Emily for who she is, yet knows that by being with her he risks losing his traditional Pakistani-Muslim family—since they believe in arranged marriage. He pushes Emily away to deal with this dissonance. Then… she falls into a coma! Ironically enough, this is what sets Kumail off on the path of love and self-discovery. Ultimately, both films culminate in the characters actually changing one of their beliefs in order to reconcile with this dissonance, and this sets them free. Matt—John and Joey’s most steadfast opponent—describes, in a final monologue, how despite all the arguments that could be made against their getting married, “the only thing that matters is what they feel, and how much they feel for each other.” In The Big Sick, the catharsis comes as Kumail visits his family for dinner after their falling out. As they give him the silent treatment, Kumail (ever the comedian) brings out conversation cards that illustrate how you can’t “disown” family. He’ll still love them, even if they won’t speak to him. Later, though his mother refuses to look at him before he moves to New York, she displays her unconditional love for him by cooking his favorite meal for the road.

Both films approach racial/cultural tensions through the eyes of a budding romantic relationship. But the differences illustrate the evolution from old Hollywood studio storytelling to its contemporary indie-film counterpart. Kramer’s film has an omniscient POV meant to explore the reality of the situation and the many possible outcomes on the spectrum of acceptance, at a time when racial tensions were extremely high. In this sense, it’s more of a social commentary than an actual love story, which paints the relationship at its center as almost too perfect. On the other hand, The Big Sick is an intimate portrayal from Kumail’s POV, filled with nuanced moments in romantic and familial love, like his and Emily’s awkward “should-we-or-shouldn’t-we” phase, or his observation of Emily’s parents’ complicated marriage, post-infidelity. It’s these moments that put the unique love story first, with the social commentary becoming its natural byproduct. In classic Hollywood form, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? has witty, stylized dialogue sharp in its criticisms about human behavior. The Catholic monsignor, an ironic and hilarious character, delivers a biting line to Joey’s struggling father: “Rather amusing, too, to see a broken-down old phony liberal come face-to-face with his principle. Of course, I have always believed that in that fighting liberal façade, there must be some sort of reactionary bigot trying to get out.”

Putting aside for a moment the profound relevance that line has in 2017, it’s a clear example of screenwriter William Rose’s purpose. Conversely, Nanjiani and Gordon’s co-writing effort approaches dialogue in a more organic, colloquial way—without losing any of the depth behind each interaction. During one particularly cringe-worthy tiff, Emily tries to deflect Kumail’s questions about her behavior until she finally blurts out, “I have to shit, okay!?” Behind the super-awkward dialogue is a hilariously candid look at a moment every couple can relate to, one that has no regard for culture or time period. Dialogue is likewise used to illustrate tension between generations. Poitier delivers one of the most poignant lines from the 1967 film, speaking to his character’s father, a retired mailman he loves and admires but disagrees with about the black male experience: “You see yourself as a colored man. I see myself as a man.” This line resonates the same way as when Kumail finally confronts his parents in The Big Sick: “Why did you bring me here if you wanted me to not have an American life?” he asks. Both Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner and The Big Sick explore difficult issues through shared human experiences and, of course, comedy. Love, both films posit, is the one experience that brings people together—whether as a romantic couple or as a family. It’s the honest exploration of this experience that makes both of these films so effective. Film Independent promotes unique independent voices, providing a wide variety of resources to help filmmakers create and advance new work. To support our efforts with a donation, please click here and become a Member of Film Independent here.

Follow Film Independent…

Twitter YouTube Instagram Membership Upcoming Events