And I’m not alone. For many, film podcasts are an essential part of engaging with film culture as a whole. They’re how we learn about what to see and which behind-the-scenes narratives are critical to contextualizing and understanding the art we see onscreen. But what about the podcasts themselves? Here now is the first in an ongoing series of interviews with the voices behind some of the most interesting, innovative and entertaining film podcasts on the digital dial. First up is Fighting in the War Room, hosted by Vanity Fair deputy editor Katey Rich, Thrillist Entertainment Editor Matt Patches, IndieWire Senior Film Critic David Ehrlich and Geek.com blogger Dave (“Da7e”) Gonzales. The show began as a way for the four New York-based friends to air (sometimes at high volume) their wide-ranging opinions. The show also spawned a Game of Thrones-themed spinoff, hosted by Gonzales (who has since relocated to Colorado from NY) and Vanity Fair’s Joanna Robinson. Through many years, several jobs and two podcast names, the four core hosts of Fighting in the War Room have unleashed a myriad of impassioned opinions on everything from new releases to digital trends, industry business news, reality TV, awards season, VR and—yes—politics. We recently caught up with Rich, Patches, Ehrlich and Gonzales over the phone to chat about the show, how it’s changed and what film culture needs more of right now—both on- and off- the screen.

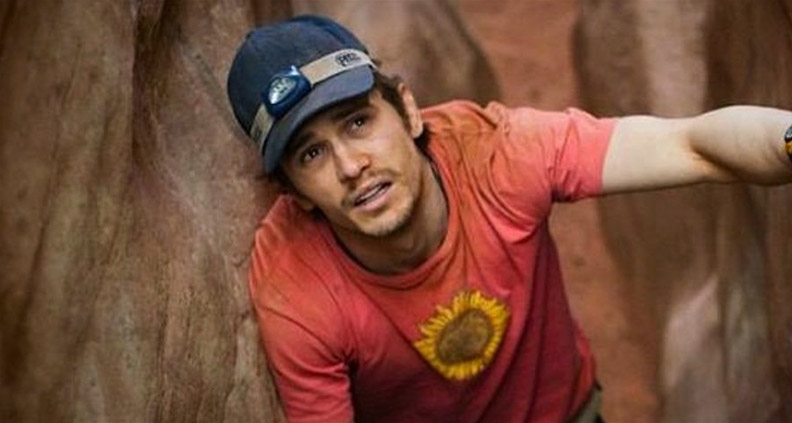

So for anyone who’s never listened before, how would you describe what Fighting in the War Room is? Ehrlich: I would say we’re a pop culture discussion podcast that began as four really good friends. We all sort of found our own niches in the industry, and as we’ve become greater friends I feel like we’ve developed a way of talking to each other that explores, at least for me, new ways of looking at film and different pop culture topics. At the beginning of each episode you typically read iTunes listener reviews, and often these reviews spend a lot of time describing what each of your “characters” is perceived to be. How aware are you of those characterizations, and do you feel you play into them at all? Gonzales: The first time that our sort of niches came up was very early on, and I think we all maybe sort of jokingly played into [that] for a while. But it’s not like I’m worried that I’m seen as the “populist superhero movie” one. Ehrlich: You know, I’ve never falsified an opinion on the show. Those are all my opinions—whether I like those opinions or not. Patches: I do think it can come off as character to people who listen to our show, because I don’t see a lot of other podcasts that are willing to have heated discussion on them. Very few of them go off the rails like we do. The other thing I like is that there’s a real diversity of opinion. A lot of film podcasts are so monochromatic in their discussions. Rich: That’s how we were sort of born, when 127 Hours came out and David hated it and Patches and I loved it. I think that’s how it started [that conversation]. We kind of did it as an audio blog—which is what we called it at the time—just because we had a different opinion and we wanted to talk about it, which is how the whole thing was born. What weren’t you hearing from other film podcasts at the time that you thought could benefit from adding your voice? Ehrlich: I think movies can be a social experience, and they have been traditionally. I think when you find people you can play off of and yell at, you want to hold that up and return to it. Patches: We’re now carrying the banner of The McLaughlin Group. Especially when things get political. How different is doing the show now versus when you first started? Obviously people’s lives change in ways that may not be conducive to keeping up an extracurricular project like a podcast. Rich: One of the biggest changes [that’s happened] is that we’ve all moved in with our significant others. That’s happened over the course of the podcast, and it’s been a lot of, like, recording after they go to bed or after we eat dinner. Or waiting until they go to bed, otherwise you’ll be recording in the same room. And I’ve had to figure out how to podcast with a baby. So far, it’s mostly working around the schedules of our significant others and spouses. Gonzales: [For me] the move to another location wasn’t that different, because even when we were all in New York we would go to screenings where we were all there and we’d have to leave immediately after to get on the subway in order to all get home around the same time to get on Skype and record. I think [being in a different city] has actually helped the podcast, in that I was doing a lot of live discovery of [the co-hosts’] actual opinions on air. But it’s really nice to have a record of something you’re doing every week with a group of people you love. All of you have successful careers and day jobs as writers and film critics. I’m curious, what percentage of people who you interact with professionally knows you primarily from the podcast? Ehrlich: I find that it doesn’t come up very much amongst my colleagues, but when I go to film festivals and meet people that maybe don’t live in New York, they often—and always to my great surprise—lead with the fact that they listen to the podcast, which is where my less calculated and articulate self lives. It’s a scary proposition. But I’m always pleasantly surprised. Rich: That’s always uneasy—pretending no one else listens. I do every once and a while so I can feel more comfortable. But it’s always such a pleasant surprise. I fondly remember seeing The Force Awakens at the Ziegfeld Theater the last time it was open and being approached by a fan of the podcast, which was really delightful. Gonzales: I kind of get noticed at conventions or something where I’m talking really loud. When that’s happened, it’s always been extremely positive. I never get any negative blowback from [the podcast], for sure. Patches: The people who @ message me on Twitter who’ve read my work don’t use my name and are just screaming obscenities at me. Versus the people who listen to our podcast and are screaming at me, who use my name and seem to have more nuanced arguments against me. Two-part question: what does each of you feel we need more of in 1) the film podcast world, and 2) film in general? Ehrlich: Unless it’s [Karina Longworth’s] You Must Remember This, I tend to not want to listen to film podcasts because too much of my world is already occupied by film. But I think we [FITWR] have the map cornered on chaos. I think that just as a listener, I wouldn’t mind listening to more pre-written, well-researched podcasts about movies in ways that approach films in ways I would not naturally. And film in general? Oh, I don’t know. There are so many things to choose from. Patches: Fewer Marvel movies! Ehrlich: No, I’d say more studio movies that cost less. The film world is divided right now between mega blockbusters and micro-budget film, and the middle has completely fallen out. So it’s heartening that something like The Girl on the Train on a $45 million budget—which is not terribly expensive relative to other studio films—do well at the box office. I would like to see more 20, 25, 30 million dollar movies. Patches: We sort of joke complain about it, that oh, here’s a new TV show… here are 18 Westworld podcasts that talk about this show and they’re all kind of the same. I think now the production value can go up. People need to think personally about what really interests them and boil that down to a structure, the same way you would make a film. What do I want to see in movies? Just more personal stories. And that doesn’t need to be autobiographical. You know, I can’t wait for people to see Moonlight, which feels incubated in a very personal experience. Rich: I don’t want to be the second person to only love You Must Remember This, but the way that [that show] brings old Hollywood stories to life and implies connections to the modern day, I think there’s a way to do that that isn’t necessarily as rigorously researched. I know there are a lot of film historians out there, and I think there’s a way to incorporate that knowledge. I’m really interested in bringing in [that idea of] what’s old is new again in a way that explores how the industry works. I was also going to use Moonlight as an example of what to do. More glamor shots of actors allowed to look interesting and attention to faces and onscreen charisma. I miss that and movies like Moonlight really bring that out. Gonzales: I think what the podcast sphere needs more now is more financial backing, because we were very fortunate to strike out on our own and to continue all doing our own thing, but there are also great podcasts that get let go for being too complex to produce. You kind of feel like, why not put some money behind a product and stick to that product until it’s done? Film-wise, what I’m looking for is a solution I don’t really have a firm grasp on yet, but [we need] more of a digital experience around mid-budget movies. That’s partially what our podcast was born out of, and that’s what still has me watching movies on opening weekend, because I know that’s when the pinnacle of conversation is going to happen. So many [films] are leaving the conversation without being interrogated properly. I don’t know what that answer is, but if someone can find a way of making community experiences around mid-budget films again, that’s it. Not a Member of Film Independent yet? Become one today to vote for the 2017 Film Independent Spirit Awards. Want more? Follow us on Twitter, Facebook and on our YouTube channel.