May is for Members! This week only: 10% off General Membership. This month, we’re celebrating our Membership experience for filmmakers and film lovers all over the globe. All month-long you can enjoy an array of special discounts on Membership. This week, you can join and save 10% on all levels of General Membership. Join or renew today!

Growing up in the wake of the Iranian Cultural Revolution of the early 1980s, nonfiction filmmaker and Film Independent Member Nazanin Nematollahi quickly came to realize her ambitions placed her at odds with her country’s rapidly diminishing protections for both women and artists. Having already begun to experiment with filmmaking as a university student at the time of the Green Movement, Nematollahi and her partner immigrated to the United States. Eager to use her filmmaking talents for education and advocacy, Nematollahi’s lens turned toward documentary, focusing on stories of protest, empowerment and autonomy. In the course of work (including co-founding production shingle More Equal Films), the current San Francisco resident became an activated member of the independent film community, engaged with a wide variety of arts organizations including—you guessed it!—Film Independent. We mounting civil rights tensions once again flaring up inside Iran, Nematollahi has again diverted her attentions to social justice—a sacrifice that has impacted the production of two feature projects, Tehran MoCA and My Body, Your Soul. We caught up with Nematollahi as part of our regular Member Lens spotlight to learn more.

NAZANIN NEMATOLLAHI

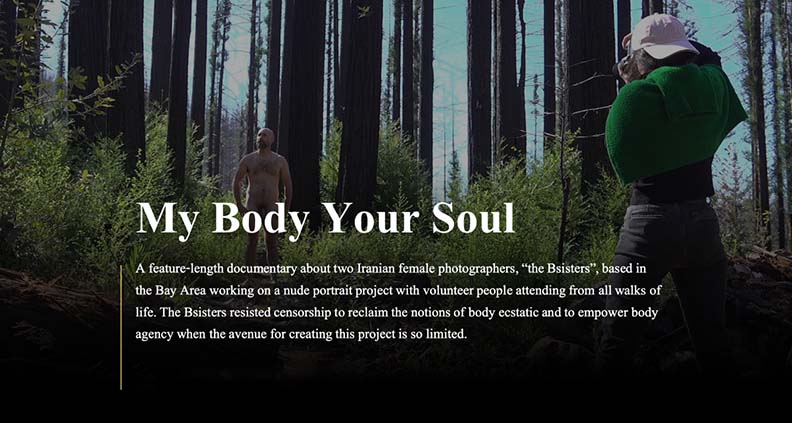

Describe your upbringing in post-revolution Iran. What was your early experience with cinema like in that environment? Nematollahi: After the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Iranian had to deal with an authoritarian and anti-West government that saw no benefit in cultural exchange or creation of any sort of art that didn’t draw attention to Islamic ideologies. Due to the heavy propaganda and censorship, visual artists, especially filmmakers, suffered the most. Throughout these years, the government banned many filmmakers from developing projects that showed the deficiency of the government or shed light on human rights issues in Iran. Excessive incarcerations, torture and threats made many Iranian filmmakers not develop projects or—sadly—accept a volunteer exile. Even though I was raised in a less cultural family dealing with the trauma of losing two young sons in the Iran-Iraq war, I was always curious about what was happening outside Iran’s borders. In such a closed country with limited internet access, I remember smuggling movies and books with immense fear of not getting caught. You know that limitation could be a way to creativity! When I met my now husband and creative partner at Tehran University, we dared to go against the tide and make movies. Despite many financial barriers, we finally bought very modest equipment, and I started exploring filmmaking. During the Green Movement in 2019, I truly understood how the regime could brutally torture innocent people. That was when we decided to accept there was no other way than to leave our motherland. Did you have an idea growing up what you wanted to do for a living or what you wanted—or expected—your adult life would look like? Nematollahi: I have always been critical of Iran’s education system and teaching methods. Growing up, I wanted to be an educator to provide quality education to the next generation. As an athletic and energetic kid, I decided to study PE and Sports Science and became a teacher and sports instructor. In that misogynistic environment, the sports scene for women was horrifying. My next shot was becoming a flight attendant to travel outside Iran. Another disappointment! In searching for my future career and with my husband’s encouragement, I produced some of his short films. We got accepted at the SFSU Cinema department through those films and moved to the US. As a storyteller, what drew you toward nonfiction film and documentary? Nematollahi: We moved to the US in 2015. I did all sorts of service jobs to meet our financial needs. A few years later, I returned to school and studied Social Justice and Equity in Education to satisfy my passion for advocating for the next generation as an educator and policymaker. During my time in grad school, I gathered that even in a first-world country like the US pushing for more equitable educational access is so complicated and not even on the horizon, and my gravitation toward documentaries stems from this issue. I decided to use the media as a more impactful platform to voice educational problems that I detect. I already had a great grasp of the documentary world and advanced my filmmaking skills by reading and participating in filmmaking gatherings and seminars, as well as making student film projects. I knew I had important stories to share, and I put energy and effort into telling those stories. When did you first become aware of Film Independent as an organization? For you, what has been the most value part of being a Film Independent Member? Nematollahi: In searching for organizations that support independent and emerging storytellers, I found Film Independent. It was one of the first organizations I contacted and asked for support. When I wrote about my story to Film Independent, they welcomed me and offered their resources for future support. I attend Film Independent film screenings and gatherings and felt their embracing environment. You know, finding a community and building a network is crucial for someone coming from other countries and lacking support and a network. I’ve been working on two feature documentaries, and I am excited to be part of the Film Independent’s excellent programs to advance my filmmaking skills and build a network of creative souls. What did the transition to the US meant for you as an artist? Nematollahi: We moved to the US without knowing a single person. The transition was so challenging in terms of language and cultural barriers and financial difficulties. As an artist, I had to find my footing and overcome my fear of pitching my ideas. However, I am grateful to be able to exercise my freedom of expression. The filmmaking world in the US is so competitive and navigating the right path is so challenging for a newcomer. I am a hardworking person by nature, and I am trying to find seasoned mentors and be part of fellowship programs to receive guidance and feedback. I understand you have two nonfiction features underway that have been greatly impacted by current events. Please describe what’s happening. Nematollahi: My projects illuminate the profound human rights issues in Iran. As an artist, I have the duty of raising awareness and shedding light on issues I have hands-on experience with. The trauma and anxiety around the recent turmoil in Iran have been hunting my soul for the past few months. All my family members are in Iran and protesting on the streets. Due to the internet shutdown, I couldn’t communicate and learn about their safety for almost three weeks at the beginning of the crackdown. I suffered from several panic attacks during these three months. I was about to lunch a crowdfunding campaign for one of my projects, Tehran MoCA, but I had the challenge of maintaining even my emotional health, let alone thinking about my project. My other project, My Body Your Soul, is about two female Iranian artists and their quest for bodily autonomy while challenging mandatory hijab. This project is experiencing a groundbreaking advancement due to the current event, as the project’s protagonists are heavily involved with the recent movement. I am adding more related material to this project and hope to finish the project by summer. This timely and crucial project can shed light on why this women-led revolution is happening in Iran. What resources are available for people who are interested in helping or learning more about the situation in Iran? Nematollahi: Many human rights advocates devote their time and energy to raising awareness about this movement. Iranians inside Iran are voiceless and under the massive attack by the regime. To be their voice, please share their bravery in your social media accounts, contact your local officials, support human rights advocates and artists who facilitate a conversation about the movement, and sign petitions. The regime has started the mass incarcerations and executions of bright young Iranian to spread fear among the protestors. International abandonment and silence are forms of violence. To keep the regime accountable, there is no other way of holding the government responsive on the international scene. Be sensitive to the systematic oppression and marginalization of women and ethnic, religious, and sexual minorities in Iran and the Middle East. Follow @amnestyIran, @nazaninboniadi, @middleeastmatters, @iraniandiasporacollective, and amplify the stories they share with the hashtag #Woman.Life.Freedom Why do you think it’s important for people to engage with and support arts organizations like Film Independent? Nematollahi: Supporting and engaging with organizations such as Film Independent is incredibly important. These organizations are working hard to support and provide opportunities for underprivileged talents. Film Independent, with the support of donors and members, provide an opportunity for the new generation of storytellers to find their footing and be bold. Become a member and partake in the future of the media industry.

Film Independent promotes unique independent voices by helping filmmakers create and advance new work. To become a Member of Film Independent, just click here. To support us with a donation, click here.

Keep up with Film Independent…

Twitter Instagram Facebook YouTube Events Letterboxd Newsletter

(Header: Tehran MoCA)