Then again, there’s nothing commonplace about the career of Scottish auteur Lynne Ramsay or her latest: the hyper-violent hitman thriller, You Were Never Really Here. The film—which earned star Joaquin Phoenix the Cannes Best Actor prize alongside Best Screenplay for Ramsay—is now in limited release, expanding on April 20. So gird your stomachs accordingly. On April 5, You Were Never Here screened at Film Independent at LACMA, at a free Members-only event, followed by an in-depth Q&A between the enigmatic Ramsay and program curator Elvis Mitchell. The discussion touched on the entirety of Ramsay’s career (1999’s Ratcatcher, 2002’s Morvern Callar and 2011’s We Need To Talk about Kevin) but focused primarily on Never Here—and there was plenty to talk about.

STORYTELLING AND SOURCE MATERIAL

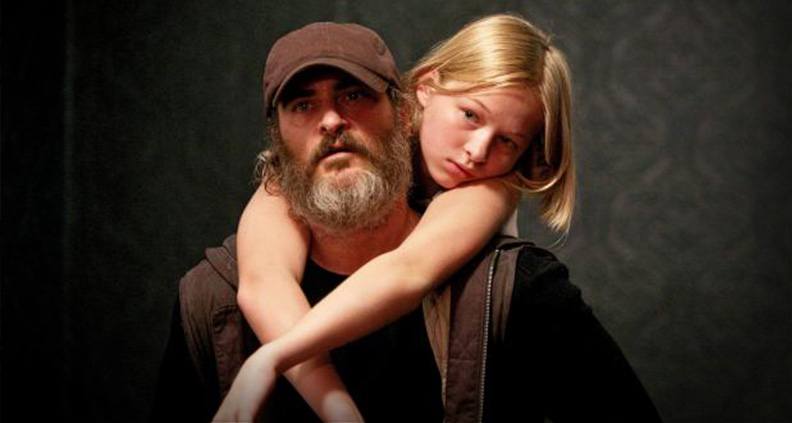

Kicking things off, Mitchell asked about Never Here’s opening image: depressed vet-turned-contract-killer Joe (Phoenix), gasping for breath inside a plastic bag he has tied around his own head—an act, it seems, part of some sort of masochistic self-harm ritual rooted in his abusive childhood. “After a couple of drafts of the script, I realized [the story] was about suffocation. About not being able to get out of your life,” said the filmmaker, in her endearingly impenetrable Scottish accent. The story—which Ramsay adapted from a then-unpublished Jonathan Ames novel of the same name—follows Joe’s deterioration as he embarks on an ill-fated mission to extract the daughter of a local New York State politician (Ekaterina Samsonov) from a child sex ring. Ames’ original version of the story went into far greater detail about the criminal conspiracy behind the human trafficking plot, complete with an extensive Mafia side-story largely absent from the final film. Initially struggling with how to adapt the material to her more atmospheric style of filmmaking, Ramsay credited a late breaking “brainwave” for her decision to pare the story down to its essentials. “Let’s just get to the girl,” she said, eschewing everything else. “A book’s a book and a film’s a film,” she said. “They’re different beasts.”

WORKING WITH JOAQUIN PHOENIX

Ramsay recalled that in their first meeting together, Phoenix told her: “I can only understand about 50% of what you’re saying.” The filmmaker joked that whenever the actor failed to understand something she’d said, he’d offer a simple “yeah” in response—this being how she eventually “tricked” him into doing the film, a stroke of luck since Phoenix is whom Ramsay envisioned as Joe from the very beginning. “I felt like it was a bit like that with Samantha Morten in Morvern Callar,” she said, referring the titular lead of her sophomore feature. “He’s the best actor out there I think,” Ramsay said of her leading man. I know he’s quite choosy. I telepathically willed him into this.” For his part, the actor bulked up with 40 pounds of raw muscle for the roll. “He was building that body and becoming a physical presence. It was like body armor—the bloody Hunchback of Notre Dame!” she laughed. Mitchell noted that while Joe is in many ways quite different than Ramsay’s prior (largely female) subjects, he still saw a consistent through-line of psychological damage and self-destruction. Said Ramsay of her filmography: “They’ve all been character studies, but quite complex characters.”

THE SCIENCE OF SOUND DESIGN

Since Ratcatcher, Ramsay’s innovative use of sound has been unparalleled among modern filmmakers. “I think I’m a frustrated musician or sound mixer,” she said. “It’s so underrated what sound does. It always used to surprise me when people do a rough cut with no mix.” Ramsay said that she always tries, when she can, to hire a sound designer to begin working on her films from the beginning. “I like to think about everything all at once,” she said. Ramsay’s attention to sonic detail extended to the film’s use of music, which features original score from Radiohead’s Johnny Greenwood (Phantom Thread, There Will Be Blood). “I would gradually send reels to Johnny,” said Ramsay, “[he] would add as he goes.” Mitchell praised the film’s use of incidental music—in one scene, a moment of exceptionally upsetting violence, incongruously set to easy listening singer Charlene’s saccharine 1977 pop hit “I’ve Never Been to Me.” “You can’t control what’s on the radio,” Ramsay explained.

VIOLENCE, VIOLENCE AND MORE VIOLENCE

You Were Never Really Here is already famous for its gruesome brutality, made all the more effective in the film by being at times only briefly-glimpsed. “I think because you see quite a lot of violence, it becomes almost banal,” said Ramsay. The filmmaker was inspired, she said, by the vérité depiction of violence in British social realist director Alan Clarke’s films. “If you hit someone with a hammer, they fall down quite quickly, right?” she asked, (probably) rhetorically. Mitchell said that the film reminded him of Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. “That’s really flattering, but you’re really setting yourself for a fall, comparing yourself to Taxi Driver,” Ramsay said. Of Never Here, she said: “It’s really about the violence in his [Joe’s] head, a psychological violence.” “I actually don’t like violence,” she said.

Coming up at Film Independent at LACMA…

Free Screening: United Shades of America (free Member screening of a episode of the CNN series, followed by a Q&A with host W. Kamau Bell) April 19 Head 35mm film screening(featuring a screening of the 1968 Bob Rafelson cult classic, starring The Monkeys) April 26

To learn more about Film Independent at LACMA click here. Not a Member yet? Become one today. Film Independent at LACMA is sponsored by Premier Sponsor Audi, Principal Sponsor SHOWTIME®, Promotional Sponsor KCRW, and Official Photographer WireImage.