If growing up you dreamed of becoming a writer, chances are you probably imagined yourself as some kind of very rich, very-famous novelist-journalist-humorist-playwrite-poet-screenwriter-cartoonist hybrid (or maybe that was just us.) In any event, your dramatist urges likely pointed somewhere other than videogames—which, in retrospect, was probably a huge mistake. Games are, of course, a multi-billion dollar industry and a maturing creative medium capable now of telling hugely complex, emotional stories on par with any other art form. What’s not always clear to those of us from more traditional writing backgrounds is just how exactly game writing works. To find out we reached out to one of the most prestigious game writers in the biz: Susan O’Connor, whose portfolio includes titles such as Tomb Raider, BioShock, Far Cry 2 and dozens of others. Luckily, O’Connor is used to answering such basics—she also currently teaches game writing at the University of Texas, in her hometown of Austin. Here’s the conversation:

SUSAN O’CONNOR

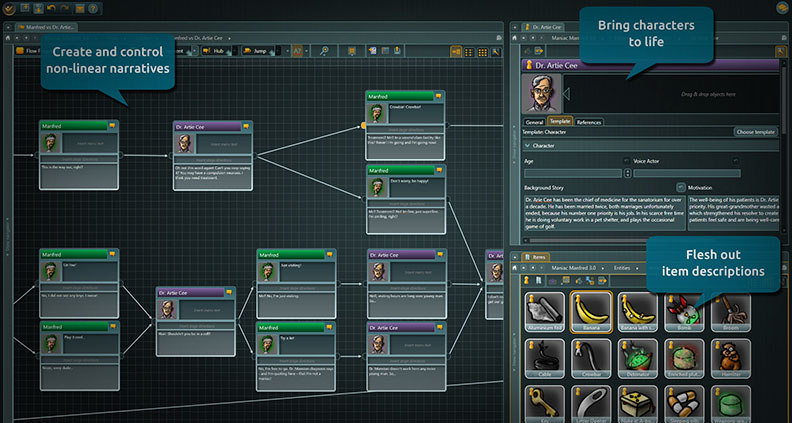

I’ll warn you in advance, I know very little about videogame development so these questions might be pretty remedial. O’Connor: Don’t feel bad about that. Honestly, one of the biggest barriers that people get in their heads about this is that no one asks questions for fear of looking dumb. So there are no dumb questions. To start, could you tell us a little bit about your relationship to gaming and writing and how the two started to intersect? O’Connor: I always knew I wanted to be a writer, that was on the agenda since, like, age four. I also knew that I didn’t want to write a novel, so I was thinking about film and TV. But I was happy in Austin and was, like: Do I really have to leave? There was a small studio here in town that was making kids games. My first project was a slumber party game for girls—it was super silly, but it was fun. I was being paid to be a writer and I was getting in on this new medium that definitely was a hot mess when it came to storytelling. It had nowhere to go but up. My career just sort of coincided with consoles and I had some opportunities to work on some amazing projects. And one thing led to another. What does a videogame script actually look like? What sort of information is on the page? O’Connor: This is the #1 question I get. I actually wrote a blog about this. The short version is: there’s the cut scene script, and there’s the in-game script—this is a gross generalization, but basically it’s true most of the time. A cut scene script looks exactly like a film script: same software, same rules, same everything. How is the in-game storytelling process is different? O’Connor: In in-game storytelling anything goes. Any line could play at any time. It’s almost like you just have to come up with scenarios and then stuff could happen at any point, triggered by what the player does or doesn’t do. It gets really complicated really fast. I think probably the best way to answer that question is to look at some of the scriptwriting software, like Articy. Is it too simple to say it’s sort of like a choose-your-own adventure type thing? O’Connor: It is too simple. I mean, the DNA is correct. There’s a free tool called Twine that I encourage my students to use, to create a playable story. It’s useful not just for applying to jobs, but it’s also a great tool that writers can use in a studio to prototype story ideas to share with designers. Like, “Here’s how a story sequence could play out in a game.” At what point does the writer typically come into the process when a game is being developed? O’Connor: The key thing about a game—and this was very hard for me to accept for a long time—is that if you create a game with a great story and bad gameplay, you will fail. But if you make a game with a real dopey story and great gameplay, it’s gonna sell a bazillion dollars. You’ve got to acknowledge the medium, and games are a kinetic medium. Meaning the story is what the player does. So gameplay and game mechanics are your #1 job if you’re a studio. And then, at some point, you’re going to bring the story stuff in. And studios are notorious for waiting way too late to bring story in, because the process of what it takes to create a story is a real black box for a lot of game developers. Is that ever frustrating? O’Connor: Like you wouldn’t believe! [laughs] It’s frustrating until you say to yourself, “This is a challenge; I’m going to crack this puzzle.” But if you’re coming from a medium like screenwriting you have to know up front that there’s going to be some unlearning that’s going to have to happen. But we’re in a period of innovation now, we’ve reached this critical mass where the audience is really ready for awesome stories—partly because they’ve stuck with games. People don’t age out of games. They play at all ages, and they want content that can keep up with them. How would an aspiring game writer start working in this field? O’Connor: I think it’s a lot easier to find work in games than it its in film and TV, because film and TV have invested a lot of time and energy in the idea of gatekeepers. Game studios just want to find the right person for the job. It’s much more of a nerd meritocracy. The things studios look for in writers are: Can you write? Not everybody can. And do you know games? The third question is: Can you get along with people? Because it’s such a collaborative process, you’re not just sitting in a room alone like a screenwriter. You’re going back and forth with people on an hourly basis about all kinds of stuff. What resources would you recommend? O’Connor: In terms of finding jobs, basically there are a couple different ways. You can certainly find job listings online—studios do sometimes list jobs on their own websites or sites like remotegamesjobs.com. Also, just like in every other industry, it also comes down to knowing people and building up that network. Game people are extremely online. Way more than film people, probably. So I would get on Twitter and I would make a list of people and start to follow them. I would join the International Game Developers Association [IGDA.org], they have chapters in every city in the world, and they’re always doing stuff online. Last question, for you personally, what’s your favorite project you’ve ever worked on? O’Connor: There are projects that I was involved with that really opened my eyes to what was possible in games. BioShock was a game-changer for me. It was one of the first ones where I was like, “Oh my god, games can 100% deliver a great story, and anyone who thinks they can’t are idiots.” The big takeaway for me about game writing is that it’s just this endless journey of discovery. It involves so many different facets. You have all these incredible tools for creating an emotional journey for the players that can’t be replicated in any other medium. And once you figure that out, that’s when something really magical happens.

To learn more about Susan O’Connor and her work, please visit her website Film Independent promotes unique independent voices by helping filmmakers create and advance new work. To become a Member of Film Independent, just click here. To support us with a donation, click here.

More Film Independent…

Twitter Instagram Facebook YouTube Upcoming Events

(Header: BioShock)