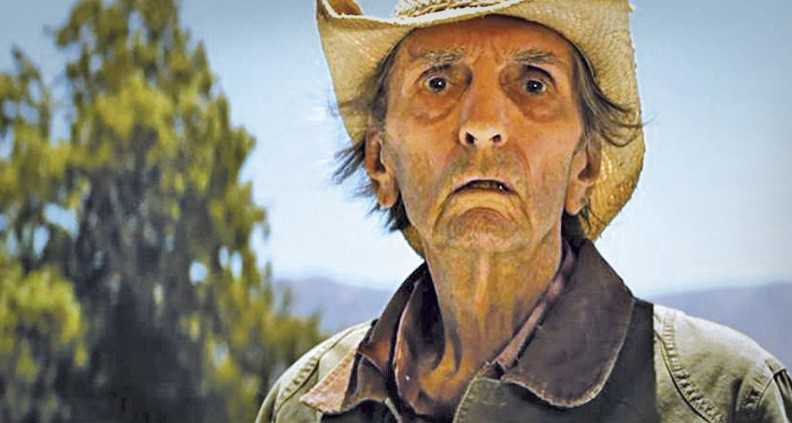

I sat down with producers John Lang, Adam Hendricks and Greg Gilreath—the trio behind the company Divide/Conquer, best known for producing Lucky starring Harry Dean Stanton, which premiered at the 2017 SXSW Film Festival. DIVIDE/CONQUER is one of the most prolific production companies in the independent space, having produced over a dozen feature films and countless short-form content in the span of only five years. We discussed how producers are able to take bigger risks than directors, and how we need to be aware and adapt in order to take advantage of the changing landscape: Rebecca Green: I don’t think I know of a company that has a more fitting name than the three of you have with Divide/Conquer. I first met Adam and John when you were Fellows in the Sundance Creative Producing Lab. But you had only produced shorts and commercials at that point, right? John Lang: Adam and I had been producing commercials and shorts for about two years. Our first feature, Like.Share.Follow., wasn’t made until about 18 months after we went through the lab. We did the math recently and tallied up that we’ve worked on over 90 projects together. It was just Adam and I at first, and then Greg joined up shortly into starting V/H/S: Viral. At first we split everything [together], but it quickly went from all three of us on one production to each of us as individuals overseeing a production and reporting back to the other two. Greg Gilreath: The volume was all about necessity. Thinking we have to say “yes” to everything and do as much as we could to build up our resumes and reputation. Green: And now you have a full company and staff. Adam Hendricks: And we have a fourth partner now. His name’s Zac Locke. He’s the former Head of Business Affairs at Blumhouse. Zac operates as a COO type, overseeing the legal, accounting and administration. Amongst the four of us we talk about this idea of an infinite expansion, the ability to always be able to say “yes” by either dividing up responsibilities or by bringing on more people. With this model, not only do we produce more, but we also create pathways for PAs to become coordinators and for coordinators to become production managers and eventually produce with us. The thing that excites us about being producers is you get the opportunity to make anything. You can do film and television, you can do stories of all genres, from all sorts of different voices. Gilreath: As a producer, nobody talks about your next movie produced being an evolution and building on your last project, or evolving your voice. Producers don’t get pigeonholed like directors do in, “Oh you did this one thing pretty well, now do that same exact thing again but this time better.” Green: I think that’s an interesting perspective. I’ve always looked at it in the opposite way, that it’s a negative that I am not working in a specific genre and therefore not building a brand for myself. Gilreath: If you really think about it, very few producers have a strong brand identity. Jason Blum, for example, probably has the strongest producer brand of anybody working right now. Hendricks: What we’re hoping is we have a brand where industry people go, “Oh, those Divide and Conquer guys, they’re good, they’re dependable, we like what they do, we like how they operate, we like the filmmakers they bring to the table.” Lang: “Their movies are good, they’re fun to work with, they come in on budget.” Green: With all three of you acting as lead producers I’m curious to know how you pick projects. Do all three of you have to love it? Lang: We actually don’t view every project through the prism of “Do we love this, do we not love this?” We always talk about three categories: is it something we love, is it something where we can make money, or is it something where there’s an interesting relationship to be gained? Hendricks: A key point on one project could be working with a new financier that we really like, whereas on another, it might be working with a filmmaker that we like. In the case of Lucky, that project checked off multiple boxes. We believed it was a film that could travel and give us a reputation and sure enough, we’ve done 15 films and Lucky has given us the highest reputation. Green: And you got to work with a great financing partner. Gilreal: Yes, Danielle Renfrew at Superlative Films. Lang: It was a great script, but it was a small film that we knew would be tough, and it didn’t earn us a lot of money. But we thought, maybe the one sure thing that will come out of this is a good working relationship with Danielle. Hendricks: Another difference between producers and directors is that if a director has a movie that fails, it might have a major impact on their next project in a negative way. But as producers, we have the opportunity to take multiple swings. We get the opportunity to take big risks knowing that at the end of the day, you can move on and produce something new and not get locked up. Lang: We look at projects we’re considering through that prism, too. In all honestly, we’ve taken on scripts that one or two of us really don’t think is very strong, but there are other factors coming into play that make it worth taking the chance on. Especially if one of us really believes in it. And really, I’ve got to say, every time we’ve felt that way about a script, the final product ended up turning out better than we anticipated. Hendricks: People tend to say if the script is broken, the film is broken. And, sometimes that is true, but in our experience, that isn’t always the case. Lang: It depends on what the problem is. Hendricks: We’ve witnessed multiple times where a good filmmaker has taken a not-so-great script and elevated it; then actors gets their hands on it and they elevate it; then talented department heads take the script and they elevate it. We’ve seen all sorts of mediocre scripts become really great final products. It’s a weird fallacy in this industry that you think you have to overdevelop something, because if it’s not at 100% no one else is going to get it there. We also ask: “What is the pathway to financing?” The last thing we want to do is waste a filmmaker’s time trying to get something made that deep down we know we don’t have the resources to pull off. A lot of times we don’t look at films that are high budget. We don’t look at films that we can’t see how we’d be able to attach an actor or bring it to the appropriate financing entities. It’s not because we don’t want to make it, it’s because it would be unfair to the filmmaker to lock their script up when we know we’re not the ones that can get it made. Green: I feel the same. With each project I take on, I’ve learned I’m the one that wakes up every morning with that responsibility to the filmmaker to make it all happen. When I first started, I didn’t know what that felt like. Not being able to deliver on what you set out to accomplish is the worst possible feeling for me, and now that I know what that feels like. I’m very cautious in what I take on. Gilreath: We call it the rocks and the hills. Are you going to carry that rock up the hill? How much energy do you have to carry multiple boulders? So we really try to pair down and be very selective about the things that we’re taking from [pre-production] all the way through finishing. Hendricks: We don’t have a slate of projects we’re developing from ground zero. We just have a select few projects where we will kill ourselves for as long as it takes to get them made. Green: How do projects come to you? Hendricks: Early on, it was like look, we’re going to be the creative producers, quote, unquote. I hate that expression. But on top of that, we’ll handle the physical production and will be your post supervisor and see the film all the way through. And so early on, that’s how we got things coming to us. Because people needed someone to run physical production, and we earned their trust. Lang: …and articulated that we understood the intersection between the dollars and cents and the physical production and the creative. Hendricks: So that’s number one. Number two is working with a lot of writers and directors. Not just on features, but shorts and commercials, music videos. Building these relationships early. We made it a mission to work with writers, directors, actors that we really liked and brought them on to commercials. We use Mike Mohan as the best example, where we hired him on a commercial which then lead to us producing his short Pink Grapefruit, which premiered at Sundance. Third, it’s been really important for us to try and find out what the financiers that we want to work with are working on and to see if we can help them; if we could be a value-add. I find it so strange that for producers, every time we take on a new project the first thing we do is call the financiers, all of them. And really, what you’re kind of saying to them is: “Hey, I’ve got this thing, and you’re going to give me a bunch of money, and I’m going to go off and I’m going to bring you the exact same thing I promised you in like a year-and-a-half.” And that’s crazy. Why would anyone give you money? It’s more important for us at this stage in our careers to build relationship with financiers and we’ll make as many for them as it takes to build that trust. Then at a certain point, it will be easier for us to bring them a project and for us to say, “We’re going to go off and make this” and they go, “I know these guys, and know they’ll actually deliver on their promise.” Green: I don’t think enough of us do that, because we have this idea that as producers, we’re the ones generating the content and that’s our role. In reality, financiers are most likely receiving more material than we are because they can actually get the project made financially. The perception often is that financiers have more value because they have the money. I want to go back to what Adam said about not liking the phrase “Creative Producer.” Adam, can you explain why? Hendricks: I don’t like it because it assumes there’s a way to do this job where you don’t have to do any of the hard work. I think that when a lot of people hear the phrase “creative producer,” it gives an idea that maybe I can do the things that I like doing; maybe I can give my notes on the script and look at the casting and sit there on set and not actually get my hands dirty. I think it does a disservice to the actual job of producing, because the actual job of producing is the understanding of where the creative and where the logistics meet and having an understanding of both sides and being the one that helps guide the filmmakers and the financiers through the entire movie to find the balance between both. Green: I think the phrase was coined with good intentions because many people think producers are just responsible for the logistics, so it was a reminder that producers are a creative force as well. Do you think we need credits that define the different aspects of producing knowing that some people get the credit for doing very little while others do it all? Gilreath: I think it ties to the whole rise of financiers being producers as well and I think that is where some want to distinguish the job. Lang: You’re trying defend your position in shorthand, but I’ve never had to tell someone that I’m the creative producer. Green: No, I don’t use the phrase either. Lang: You understand what I do, I understand what you do, and that we’re working with all of our strengths, everyone is contributing their strengths to get their project made. Green: Do you guys work with other producers or keep your teams internal? Hendricks: We love working with other producers. We’ve dropped the ego of needing to be the guys who find the material. Sometimes a producer is already on board before we’re on, and so we ask the same questions we ask investors, which is what do you want out of this, and then we help them get that. We’ve worked with producers who are just on because they found the script first, they don’t necessarily know how to produce start to finish, but they want to be a part of the production. Other times we’ve actually reached out to get our producer friends to come join with us so that we can expand our bandwidth. We always see bringing on other producers as added value. Green: How do you deal with decision making with so many producers involved? Lang: We often defer to the director while at the same time always voicing our opinion. If we disagree it’s not because we want it to be our way, it’s because we think that they are betraying their own vision. The big thing with us is we will never make a filmmaker take our notes. We will give arguments, we’ll go to bat for what we feel is best and sometimes we disagree with each other. Sometimes it’s a room with people having different opinions, but we want directors to take everything into consideration and then make what they feel is the best decision for the film. And once they make that decision, we go with it and we protect it. Gilreath: We also discuss between the three of us first and then have one of us present to the director. There’s a balance. We want it to be an open discussion. But at the same time, you have to somewhat be on the same page as a producing team. The one thing that we make sure that we don’t do is we don’t actively disagree with each other in front of filmmakers. If there’s a battle between us, we’re going to have that behind closed doors. Lang: I think with directors, as far as like how they accept feedback, so much of it has to do with their mentality and how they want to hear things. We work really hard early on to remind them that we’re all on the same team. I’ve been a part a of a project where the producers just knew the director would react badly to anything we said but then, three days later, we would all come back and cooler heads would prevail. We’d have a really great constructive conversation, that was just part of that director’s process. We also work with a lot of first- and second-time filmmakers and we consider it part of our job to help them become better filmmakers. Green: So they can go off and make bigger movies without you? Hendricks: The hope is they’ll bring us. It’s all about sustainability. We want to be doing this in our 40s, and our 50s and our 60s and we want to set ourselves up for that. The same with our filmmakers, we want to work with them well into their future, so we try and create an environment in which they are becoming better versions of themselves. Green: Are you actively trying to find bigger projects? Gilreath: We just did our biggest one, about $1.8 million. But everything we have on our slate that we’re trying to raise the financing for is actually bigger than that right now. We are consciously looking for projects that are sellable at the three-to-five million range. We’re very conscious about trying to take steps to get to that point while still continuing to maintain our under-two-million dollar business. This is where it helps to mentor younger producers. So when there’s a $600K dollar movie we really want to do, we can pull one of them in to act as lead producers with us being executive producers overseeing key big picture decisions such as casting and budget and script development and can then send them off and say, “Have fun in Mississippi, we’ll be here if you need anything. We’ll come visit, we trust you.” Lang: Exactly. And then once the movie is shot, we’ll give notes on the edit, we’ll help with festival strategy and selling the film, and use our relationships to make sure the film succeeds. Green: Do you have a vision for what you want DIVIDE/CONQUER to look like in five or 10 years? Lang: I think one of the things that has made us sustainable is that we really try to take the advantages that are right in front of us, that it’s not necessarily a five- or 10-year pathway. We want to move forward and we want to grow. But it’s like bowling, you want to look at those first set of arrows not the ones way down the lane. Green: Funny, I remember learning that from my aunt the first time I went bowling. To look at the arrows closet to you. Lang: Early on we thought, let’s have a mission statement, let’s say what our five- or 10-year plan is going to be. But we realized that we’ve veered away from those things because we took advantage of the opportunities that were in front of us. And for us, it’s not about becoming the company we all see in our heads, it is being conscious of the changing landscape that is this business and redefining our place within it to best take advantage of it. Green: That’s fantastic. Watch the trailer for Divide/Conquer’s upcoming feature Breakarate below:

To read this conversation as it originally appeared, click here. To read our interview with Rebecca Green about the launch of Dear Producer, click here. Learn how to become a Member of Film Independent by visiting our website. Be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram and don’t forget to subscribe to Film Independent’s YouTube channel.