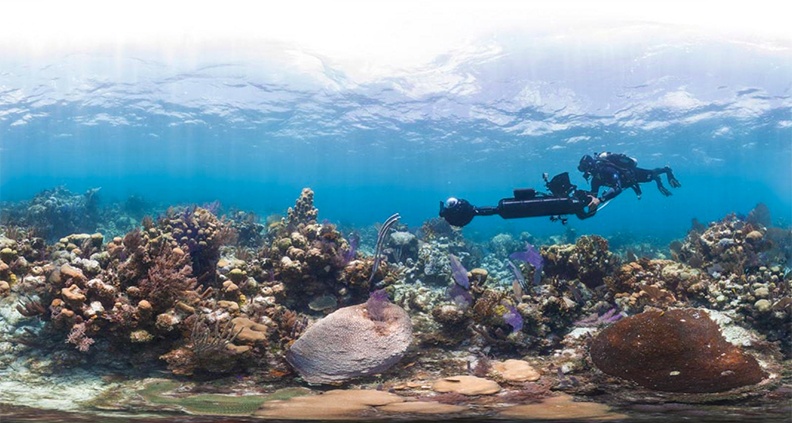

This week: Coral reefs around the world are vanishing at an unprecedented rate. In this nonfiction feature, a team of divers, photographers and scientists set out on a thrilling ocean adventure to discover why and to reveal the underwater mystery to the world.

CHASING CORAL

Type: Documentary Feature Director: Jeff Orlowski Producers: Jeff Orlowski, Larissa Rhodes Budget: Undisclosed Financing: Private Equity/Individual Donations/Grants Production: 3½ years, 2013-2016 Shooting Format: RED Dragon, RED Epic, Sony FS7, Panasonic GH4, GoPro, Canon EOS-1D C, etc. Screening Format: DCP World Premiere: Sundance 2017 Distributor: Netflix Awards: Sundance Film Festival 2017: Winner—Audience Award, US Documentary Website: www.chasingcoral.com

DEVELOPMENT AND FINANCING

Jeff Orlowski discovered filmmaking while studying anthropology in college. He’d taken an introductory documentary workshop, but it wasn’t until a lengthy stint as cinematographer for nature photographer James Balog and his Extreme Ice Survey—which attempts to document the effects of global warming on glacial ice—that Orlowski developed the confidence to make the full-length feature doc, Chasing Ice (2012). “For me, learning how to craft the story came through the post-production process,” Orlowski recalls of the two years he spent piecing the film together. He was therefore well prepared in 2013, when he and producer Larissa Rhodes received an email from Richard Vevers, founder of The Ocean Agency, a group of ex-advertisers who now devote their skills to creative advocacy for marine conservation. Vevers believed that a documentary about the devastating impact of climate change on coral reefs might be able to deliver a powerful message, and that Orlowski was the filmmaker to tell the story. Rhodes, who had never produced a full-length feature documentary before (she was the production coordinator on Chasing Ice), knew that she and Orlowski would need funds just to investigate the potential for the film Vevers was proposing. Extensive underwater filming would come with technical challenges and the team needed to figure out what production might look like. But as Rhodes points out, “For any documentary filmmaker that’s a difficult question to answer, just because you never know where the story’s going to take you.”

Orlowski can’t pinpoint a specific moment, but realized soon after meeting Vevers that, for all his understanding of climate change, he had almost no knowledge of the problem Vevers was trying to highlight—and that meant there was a story here that probably hadn’t been told. Knowing that seed money would be their biggest hurdle, the team approached several of the individual funders who had supported Chasing Ice. Orlowski knew he wanted to shoot with cutting edge 4K cameras that would capture sharper, clearer images; the initial raise from a single supporter covered the cost of a RED Epic with a premium underwater housing—and six months of production.

PRODUCTION

For roughly the first year of shooting, the crew followed Vevers and interviewed scientists who directed them toward the subject of coral bleaching—the stressful and often lethal effect of prolonged exposure to warmer temperatures, which causes coral polyps to release the algae that lives inside their tissues, turning them pure white and often killing them. “I don’t think Jeff sees himself as an activist,” Rhodes explains, “but he felt a responsibility to show the world what he had seen.” Footage from Orlowski’s first trip to Australia proved striking enough to make a sizzle reel in early 2014, which they used in the summer of 2015 to pitch through both Sundance Catalyst and Good Pitch—both of which are intended to connect projects with potential partners and supporters. Good Pitch in particular focuses on social justice films that do heavy outreach, and through it Orlowski and Rhodes met consultant Erin Sorensen of Third Stage Consulting, who helped them to design the film’s impact campaign. Later they met Samantha Wright, who came aboard as the project’s impact producer. Vevers’s team was already extensively documenting dying coral around the world—so Orlowski and Rhodes had access to a tremendous wealth of archival footage (including press materials) that would constitute a sort of introductory sequence for the film. “We got to start following Richard at a stage in his project where he already knew a lot about the oceans, but he still had some confusion around certain things—so we were able to film some really meaningful scenes that helped explain things to the audience,” Orlowski says. The team dove in—literally—undergoing extensive dive and safety training for their travels to film underwater in Bermuda and Australia. The crew was a mix of experienced underwater cinematographers and eager novices, but all had to be certified and safety protocols followed to the letter. Though Orlowski had gone diving before, he had never attempted to shoot in the ocean and was acutely aware of the risks. “When I look back through the footage from the beginning of production to the end, it’s amazing to see how the quality of the cinematography on our team improved over time,” Orlowski says of their extraordinary learning curve. Controlling one’s own body and buoyancy while holding a camera is difficult enough, but there were also challenges in learning to work with and manipulate natural light, and to add additional lighting when necessary. “We just kept meeting more experts and studying up on it,” he recalls of the process—one they realized they’d have to undertake themselves, when it became clear that employing underwater cinematography specialists exclusively would be prohibitively expensive. (Though Orlowski admits he was eager to become an expert himself.) Finding the right camera was another major undertaking, and Orlowski was shooting just as 4K technology was becoming widely accessible and semi-affordable. The team first tested an inexpensive camera that performed so poorly in low light that they sold it after a single shoot. Looking for one camera that they could use both underwater and on land, they debated between the RED Epic and the Sony F55. Based on the advice of experienced cinematographers who recommended the RED for the availability of quality underwater housings, and the fact that it would allow them to upgrade sensors without the expense of a whole new camera, they went with the RED. They also acquired a Canon EOS-1D C, but soon replaced that with a second RED. A year or so into their shoot, Sony released its FS7, which became Orlowski’s camera of choice for topside (above-water) 4K run-and-gun footage. Used to working as a one-man crew on Chasing Ice, Orlowski now found that he couldn’t move seamlessly from shooting on a boat to shooting underwater; neutrally buoyant equipment, when properly calibrated, will remain level and easily mobile in the water, but this required extra adjustment based on weight and depth. With a heavier workload than expected, he and Rhodes were compelled to grow their crew to include an additional team that could shoot topside while another dove. To capture the gradual decline of the coral, the filmmakers had spent a year developing an underwater time-lapse camera. They had built a complete system to house the camera, but quickly found that the buildup of marine life would need to be wiped off the transparent housing by a diver frequently to preserve the integrity of the images. They were therefore thrilled to discover View Into the Blue, a company that had developed an underwater dome wiper system for exactly this purpose—located, by sheer coincidence, only 10 minutes from the filmmakers’ office in Boulder, Colorado. Working with View Into the Blue, Orlowski and Rhodes refined a wiper system that would keep the underwater camera housings free from the build-up of algae, so they could continue shooting time-lapse footage of coral for months at a time; just as importantly, they met Zack Rago. Rago, a certified diver and self-proclaimed “coral nerd” was a technician at View Into the Blue. When the production’s first underwater camera installation indicated that a major bleaching event was about to happen in multiple locations, View Into the Blue sent Rago to work as part of an additional installation team. “That’s when Jeff really realized how much Zack cared about the coral. When we had a camera system that flooded, there was nobody more disappointed than Zack,” Rhodes explains. Rago became an integral part of the team, and his emotional response to coral death would have an impact not only on the filmmakers, but on audiences too, as he would become an important way into the story. In the summer of 2015, Orlowski and company installed six cameras at sites surrounding Bermuda, the Bahamas and Hawaii in anticipation of further bleaching. When they retrieved those cameras several months later, they were utterly devastated to discover that five of the six—all of which had manual-focus lenses—had shifted out of focus soon after their installation. “It was a complete shock. No one could understand why this had happened,” Rhodes remembers. Despite meticulous attention to every conceivable malfunction, the crew had encountered an obstacle they’d never even considered. Months’ worth of footage was useless and this significant blow to Orlowski’s efforts became a major part of the film’s narrative. Ironically, the one camera that had functioned was the one the team had only decided to install last-minute, using a fixed focal length lens—the only type they had available. The filmmakers and technicians now reworked their underwater camera system once again, using fixed lenses and streamlining the installation process significantly. When they installed them for the next shoot, the cameras worked perfectly. As production wore on, Orlowski and Rhodes found that whatever time they weren’t devoting to travel and shooting was occupied by editing, reviewing footage, and continued fundraising. It had always been important to Orlowski that this was a human story, and he and Rhodes had worked with editor Davis Coombe and writer Vickie Curtis to tease out character arcs that might give shape to the film. Rhodes credits Orlowski with being able to follow the action rather than steer it, though contemplating an unknown ending caused them both a good deal of stress. “There was a period on this production where we were trying to find the story and trying to figure out where the film would end,” Orlowski remembers. “In my mind, when you know the climax of the film, that’s the most important part.”

The climax presented itself when they discovered a massive bleaching event off the coast of Australia in the spring of 2016. Once they knew what they were building to, Orlowski and Rhodes focused on interviews that would fill in the gaps, as it was clear that shooting was coming to an end. But the filmmakers soon realized that the event would have an impact worldwide—and there was no way to capture the many instances of bleaching with their modest crew. “So we thought, why not ask the global community to show us what’s happening in their own backyards?” Rhodes recalls. The crew shot a brief appeal from Orlowski on an Australian beach, asking the diving and photography communities to come together and document what they were seeing; they called this the “global call,” and posted the video to YouTube and Facebook. Co-producer Stacey Piculell coordinated the follow-up and asked their scientist connections to help spread the word. The team was stunned at the response. From professional photographers to interested scientists, people from more than 50 countries submitted footage of local coral bleaching between February and June, much of which made it into the film.

FESTIVAL PREP AND STRATEGY

With so much footage and so much important scientific context to communicate to an audience, Orlowski and Rhodes were deliberate in piecing together their narrative. For every striking visual moment that was woven into the story, they asked themselves whether it advanced the story. They conducted additional interviews during the editing process to hone important information, until they felt confident of the narrative’s clarity and accessibility. The delays caused by camera failures had set the production timeline back almost a year, and though it ultimately led to a much stronger narrative, it changed the filmmakers’ expectations about festival submissions. And because they had witnessed actual coral death on a large scale, the team was feeling enormous pressure to get the film out to audiences and spread its message. They couldn’t imagine a better platform than Sundance—but that meant executing post at a breakneck pace. Happily, the film was invited to premiere at Sundance in 2017. “We were editing until a few weeks before the festival,” Rhodes admits. Josh Braun of Submarine, who had worked with Orlowski on Chasing Ice, would handle sales. Braun also connected the team with Adam Kersh and Kate Patterson of Brigade PR/Marketing, who understood that this was an adventure story with a human journey, and not just another global warming film. The film was also represented by Jonathan Gray at GKSSD.

THE SALE

Chasing Coral premiered at Sundance one day after the presidential inauguration—the same day coordinated women’s marches took place all over America. “Emotions were running high,” Rhodes remembers of the general tenor of the festival, but believes that the hopefulness of the scientists’ message was ultimately inspiring to the audience. Nearly the entire cast and much of the crew attended the premiere, and “the scientists got a standing ovation,” Rhodes says. “That was just an incredible moment for these people who have spent years trying to raise awareness of what’s happening in the oceans.” Interviews with the scientists and with Orlowski, Vevers, and Rago seemed to make an impact, and Rhodes credits the Brigade team with spreading the word that the film was focused on an underwater adventure, rather than prophesying doom. Every screening played to nearly sold-out houses, and the film had school and community screenings in Salt Lake City—which had a particular impact on Rago, who connected powerfully with the students. The film received the Documentary Audience Award at Sundance, as well as multiple offers for distribution. “We ended up partnering with Netflix, which has made the film available globally and they have been a great partner for this film,” Rhodes says. Even before they finished shooting, Orlowski and Rhodes had known they wanted to create a major impact campaign for the project, which meant they’d need to carve out rights for educational and community screenings from whatever sale they made. “We really wanted to make sure it was available as a tool to get people mobilized locally and get students excited about science.” From the start, Netflix was open to a partnership that would allow the filmmakers to pursue their impact goals, but the company also believed powerfully in delivering the film’s message to their subscriber audience. Netflix picked up worldwide rights as a Netflix Original for an undisclosed sum.

THE RELEASE

Chasing Coral was released in theaters in New York and LA and simultaneously on Netflix worldwide on July 14, 2017. Orlowski and team did Q&As at LACMA and at Soho House in New York, and in an effort to encourage subscribers to host home screenings, the filmmakers built toolkits available for download that would help to answer some frequently asked questions. They also hired and built a team of seven at Exposure Labs to handle impact, and to ensure that the film was ready to be distributed when requests came in for educational and community screenings. Their goal is to find unlikely messengers to spread the word about climate change and its solutions. Educational resources are available for download from the Chasing Coral website, and Netflix permits screenings to any classroom or assembly within a school, provided a single teacher in that school has a Netflix subscription. The producers are also in the process of building an interdisciplinary curriculum that will incorporate science, economics and communications and will help to propel local and educational initiatives for clean energy and sustainability. All these efforts cost money, of course, and have been supported by The Kendeda Fund, The Tiffany & Co. Foundation and a number of private donors. Direct donations through the Chasing Coral website have also played a role—and shown that the project is inspiring viewers all over the world to take action. (The Wild Foundation 501(c)3 provides a creative collaboration agreement to allow for donations to be tax deductible.) Today, Orlowski and Rhodes continue to be deeply committed to creating change through Chasing Coral, but with impact producer Samantha Wright continuing to lead the charge on impact, the filmmakers are beginning to look forward to their next project.

FILMMAKER ADVICE

“Find people that you love to work with. We surrounded ourselves with some of the best people—people who were better at doing things than we were,” says Rhodes. “And what I learned was that working with people you love who are passionate, talented and genuinely wonderful human beings makes an incredible family. It brought something that was a bit magical to the film.” Learn more by visiting our library of case studies for additional resources. Film Independent promotes unique independent voices by helping filmmakers create and advance new work. To support our work with a donation, please click here. Become a Member of Film Independent here.

More Film Independent…

Twitter Instagram Membership Spirit Awards