A designer designs out of the same deep, personal, dark, poorly lit (or well lit) places that any writer writes or any painter paints or any musician creates. It comes out of the same places. You can’t tell what that is really. It’s just out of who you are and what you’ve become. —Production Designer Jeannine Oppewall As mysterious and inexplicable as the creative impulse can sometimes be, there are certain specific processes and philosophies that every designer relies on and returns to again and again, no matter what the project or who the director may be. During Saturday’s “Reimagining LA: Production Design Master Class” at the Los Angeles Film Festival, Jeannine Oppewall and K.K. Barrett shared how they each approached two very different projects with very different aesthetics and time periods—one in the past and the other in the near future—that nonetheless have a significant commonality: both are set in Los Angeles. Oppewall, revealed some of the challenges and inspirations behind her work as production designer on L.A. Confidential and Barrett, who has collaborated with director Spike Jonze on all of his films, described how he achieved the unique, timeless look of Her. On how the collaboration with the director began “You start with the script, of course, and with any admonitions the director may have to give you,” said Oppewall. When she sat down to discuss L.A. Confidential with Curtis Hanson, she said, “I had the very eerie feeling I was talking with a guy about what was going to be his masterwork, and I can’t tell you why I had that feeling. I just did. It wasn’t that he was particularly impassioned, because he’s not that kind of guy. And it’s not that he said such intensely beautiful or brilliant things. He said, ‘it’s a film about how nothing is what it seems. Nothing is what it seems.’ It gives you a germ of something wonderful to work with. It starts from there, at the intersection of what the script calls for, anything the director might have in mind and who you are.” “When the director is the writer on the script,” noted Barrett, “you have to take them much more seriously than when you’re just dealing with the director and they didn’t write the material, because they’re much more invested in it, and they see it in a way as they’re writing it, and you try to extract that out of them, because they will have a vision. You try to find out what they see and how much they see.” Another starting point, said Barrett, is separating the ideas from the problems. In terms of exteriors, Barrett pointed out that for L.A. Confidential, Oppewall had to avoid what was built since, but with Her, he had to avoid what was built before. “After the problems,” he said, “you just get into ideas.”

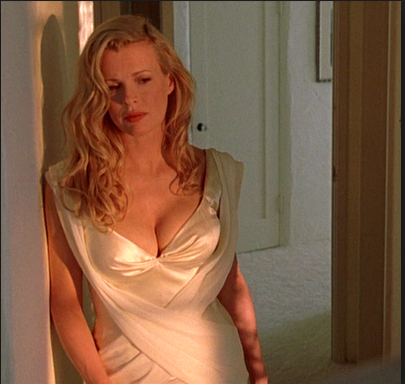

On identifying the perfect locations Oppewall spent about 10 weeks in the car with the location manager. “We would pick out neighborhoods neither of us know well,” she explained, “but had a feeling they would be worth exploring.” On weekends, Oppewall drove alone with post-its stuck to her dashboard of places she hadn’t been able to find. On each, she’d jotted the name of the location and the action that took place there. One day, she was driving down Hollywood Boulevard with a friend and shouted “Stop the car!” because she’d spotted a building that spoke to her. She jumped out of the car, ran down the street and later explained her crazy behavior to her friend: “I just found the ‘pot bust movie theater!” “You internalize the story to such a degree,” Oppewall explained, “that when something jumps out at you and says ‘Take me! Take me! I really want to be in your movie.’ It’s an interesting way of working because you do have to prime your pump and you do have to sit with it for ever and ever, and you do have to let the locations come out at you.” Barrett talked about another reason for becoming intimately familiar with the script. “You have to know the script very well because sometimes you have to bend to the action to fit a location you think is really good. If you know the reasoning of the script and the reasoning of the director, then you’re able to get into that conversation. You may not always win, but you can kind of stick your foot in the door, and then strong arm a little bit and location and maybe coming around to a location that adds to the palette of the movie.” “I had scenes in my head that I knew where they should be. I had seen a building that looked like it had elephant legs,” said Barrett. “We couldn’t figure out what to do with it. We kept going to it and loving it, and finally I said, ‘that should be the underground [where he sees the ad for the operating system].’ It made psychological sense. It made visual sense. It made story sense.” Having a film set in the near future Barrett said gave them complete freedom to choose locations solely because they liked the way they looked—so he gathered images of buildings and settings like gathering firewood. “You were able to make up everything. There were no definitive anchors. Our idea was always to shoot things in three or four cities and call it one place.” For instance, to go into the building where he lives, Theodore goes into the Pacific Design Center—that’s his lobby—ends up at 9th and Figueroa, and before that he goes through a concourse in Shanghai. One challenge for Barrett was the decision to avoid showing cars. “It was very important to us to not celebrate design advancement like technological items or cars that date a story,” he said, “nor have it be about that. It’s about characters.” On steering clear of noir “We talked about making a period movie but making it in a very contemporary way,” Oppewall explained. “There’s something very specific about Los Angeles, that you can have a sun-baked noir,” added Barrett. “It is this omnipresent sunshine and concrete. It’s not always glorious sunshine. It’s sold as glorious sunshine, but it is a kind of darkness in full sun.” “I agree,” said Oppewall. “It’s not just ‘June gloom.’ There’s something that becomes sinister about the sunshine after a while.” On the pressure to achieve perfection Oppewall described working with her set decorator on the scenes where Kim Basinger conjures Veronica Lake—as a high-end call girl in an unforgettable ivory satin gown. “That dress and that furniture…,” she said, “…it has to be soft. It has to be beautiful. It has to be theatrical. It has to be sexy.” They ultimately found what they were looking for in consignment stores in Palm Springs, she said; “It would not have been the same movie had we not found the right furniture.” Oppewall once told the set decorator, “If we fail at this, our careers are over.” Pamela Miller / Website & Grants Manager