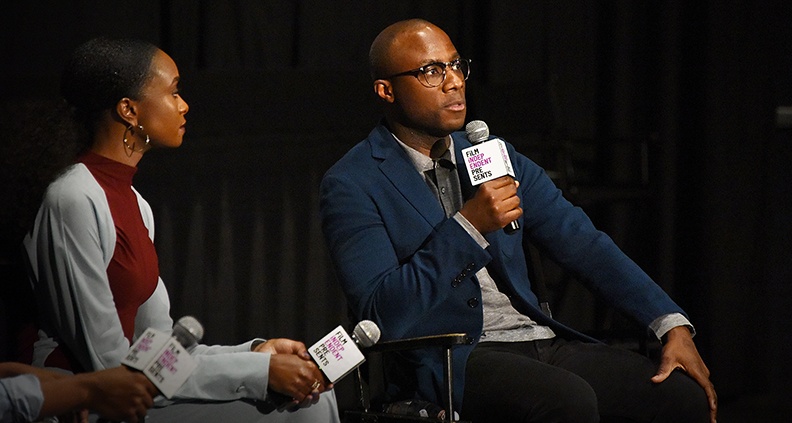

Beale Street balances themes of social injustice—race, poverty, false imprisonment—with a beautiful, moving love story. It presents its love as pure, embedded with a whisper of naivety between the film’s main characters, Tish (Kiki Layne) and Fonny (Stephan James). Tragedy interrupts the warmhearted narrative, leaving viewers to sit with a looming question throughout the duration of the film’s two hours: can Tish and Fonny’s love endure against an unfair, unforgiving and brutal justice system? All the while, Jenkins artfully explores the complexities among black families and communities, using (as with his previous films) inter-personal relationships as a channel for empathy. The film, Jenkins’ follow-up to Film Independent Spirit Award Best Feature winner Moonlight, was presented partnership with KCRW. Following the screening, Jenkins and Layne joined The Los Angeles Times film reporter Tra’vell Anderson for a Q&A. Here are some of the highlights:

‘IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK’

How did Jenkins arrive at Baldwin? Through an ex-girlfriend, actually. But regarding If Beale Street Could Talk specifically, a friend had handed Jenkins the book with the stereotypical line he said filmmakers always get: “You should read this book, there’s a movie in it.” He said, “I just saw [right away] that it was the fusion of Mr. Baldwin’s two voices: the one voice that was so diligent about capturing sensuality and romance, but was just as passionate about systemic injustice—shining a spotlight on the ways in which society and the American judicious system disenfranchises the lives and souls of black folks in America.” Layne knew from the very beginning that Jenkins’ take on Baldwin would be special. In navigating high-pressure moments on set, the first-time feature film actor said, “We created such a family, I felt like people could actually see it”—her need for some guidance and comfort when, on occasion, the going got tough, citing Jenkins and co-star Regina Hall as being especially attuned to her feelings. The first step of piecing the Beale Street’s onscreen family together was to find the film’s two driving forces: Tish and Fonny. “It’s very clear [in the book] that these two characters are soul mates,” he says, adding: “I just hadn’t seen many depictions of young black people depicted as soul mates with this very innocent, pure, lush sort of love.” “From there we wanted the chemistry to radiate outwards,” he said, in trying to build a family around Layne, and a very different one centered around James. Jenkins said that securing Regina King for the role of Sharon—Tish’s mother—was the first building block. “Where I grew up, the family tree starts with a black woman, [whereas other people] are under a patriarch,” he contends. One of the most striking lines of dialogue is when Tish’s older sister says to her, “Unbow your head, sister,” after Tish reveals pregnancy to the family early in the film. According to Layne, it speaks to a powerful message: “There can’t be any shame in a household that’s supposed to be filled with unconditional love.” Without judgment, her family recognizes that her current situation is “a result of nothing but love,” she said, quoting the film. Regarding the utility of close-ups and how empathy becomes activated through this mechanism, Jenkins said: “Sometimes I want to place the camera directly in front of [the actors] so we can have you [the audience] access directly their emotions.” For actors, he said, “When you’re looking directly into a camera, you’re only giving. But now you guys in the auditorium are directly receiving.” As Jenkins explained, when you receive Layne, James or Regina’s image staring straight at you, you can’t escape it. Empathy is activated. Watching the film is no longer a passive experience. Although it’s up to audiences to discern the meaning of “Beale Street”—street where, according to Baldwin, folks survived injustice and everything in between—for Jenkins it’s about “building families, finding love, building communities” through the chaos. “I think the book in a certain way could be retitled The Lives and Souls of Black Folks,” said Jenkins. “Because I do think that the struggle that Tish and Fonny undergo is through no cause of their own, yet you end up at the end of this story.” He described one key sequence in the film—of two black fathers committing crimes in order to bail out an innocent son who hasn’t committed a crime—as “America in a nutshell.” “And yet somehow at the end of it all, you have a family sitting around a table saying grace. So I think in a certain way, the meaning of the beating of drums is we have to keep these families together—by any means necessary,” Jenkins fittingly concluded, paraphrasing Malcolm X.

If Beale Street Could Talk opens today, December 14, in theaters nationwide, distributed by Annapurna Pictures. For more info, visit the film’s website. Learn how to become a Member of Film Independent by visiting our website. Be sure to follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram and don’t forget to subscribe to Film Independent’s YouTube channel.